Lack of capital was a major factor for the earliest planters, who had no choice but to convert their existing coffee houses into tea factories. These early conversions did not prove a success in the long term because tea production required more

space and adding extra floors was expensive.

space and adding extra floors was expensive.Dambatenne Tea Factory

As production increased, the financial problems of mechanization had to be met. It was therefore suggested that instead of each planter attempting to cure his own leaf, they should raise the capital among themselves to establish a well-equipped factory in each centre of tea cultivation in which the leaf of the district could be properly cured under skilled supervision. This would cut the cost and produce a uniform quality tea with more appeal for the buyers.

Property owners soon realized the economics of large scale production and the move led in time to the formation of limited liability companies to take over groups of estates or to work central factories involved in the curing of their own leaf and for a fixed charge the curing of leaf from neighbouring estates that could not afford the luxury of their own factories.

Although there are many ways in which the leaf of Camellia sinensis may be prepared, only three popular types of tea leaf reach the world markets: black, green and oolong. Black tea is the type for which Ceylon is noted; its particular characteristics are that the leaves are fully fermented in the process of manufacture. In the production of green tea the leaves do not undergo any fermentation at all during manufacture. Oolong is a semi-fermented tea, mostly manufactured in China.

In Ceylon, initially, tea was prepared by hand, as was done by James Taylor.

Processing tea in those days was not an enjoyable task; the leaf had to be hand rolled on tables and fired over charcoal stoves.

Processing tea in those days was not an enjoyable task; the leaf had to be hand rolled on tables and fired over charcoal stoves.Tea Manufacturing Process Display at Mackwoods Labookellie Factory

During the early stages, power to work the factory was provided by water-wheel and it was for this reason that the original tea factories were located close to streams or rivers. But this meant that factories could not be worked during periods of drought so they were forced to seek other sources of power.

This method might have continued so long as the intake of green leaf was limited, but with the rapid increase in the number of tea estates and the size of the crop and the necessary introduction of machinery in the 1880’s, tea began to be manufactured rather than prepared.

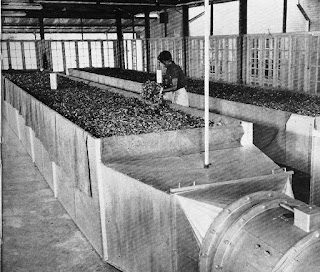

Coarse Tea Sorting In the 1880’s

Large Tea Factories were built at all altitudes, as part of a tea estate, in order to reduce the time between plucking and processing the leaf to a minimum. The steam engine became widely used until the internal combustion engine was introduced.

The manipulation and curing of the tea leaf are the most difficult part of the tea planter’s work and the value of the manufactured tea depends entirely upon the skill and care with which this is done. Leaf grown under the most favourable conditions of climate and soil will be unacceptable to the consumer if the curing is defective.

The cultivation and manufacture of Ceylon Tea is marked by an insistence on the purity and unadulterated quality of the product and from inception of the industry, Ceylon has been known for ensuring that the doubtful nature of some of the early blends were completely eliminated.

Weighing Tea Leaves

The tea as plucked from the bush even on dry days consists of about seventy-five percent of moisture, a percentage of this moisture varying from thirty to forty percent, depending on whether the weather is damp or dry, requires to be extracted from the leaf by withering before the fibre of the leaf and stalk will stand the strain of rolling. When transporting leaf to the factory every care is required to be exercised, not to allow fermentation to commence, also the leaf may be damaged unless carefully handled. When the leaf arrives at the factory it is quickly weighed and then spread evenly and ‘fluffed’ on tats or troughs stretching the whole length of the upper floors where there is a flow of air. The troughs have a perforated base and air passed through it reduces the excess moisture in the leaf to about 60% to 70% to make it pliable.

Early factory withering loft

The process in known as withering; the time required for the leaf to reach the correct condition depends on temperature and humidity and will range from eighteen to twenty-four hours in different seasons and districts. During the wet season or in humid areas, the optimum conditions are obtained artificially by directing heated air through the loft with fans.

During withering, physical and chemical changes take place in the leaf. The chemical changes that take place during withering, materially increase the flavour and strength of the finished product. The process must be carefully watched, because over-withering can lead to poor quality tea.

When it has reached the correct degree of wither, the leaf is rolled, twisted and at the same time slowly broken up. In the early days of the tea industry, the leaf was rolled between coolies hands with a slightly concentric motion. In dealing with large crops this hand rolling was found to be too lengthy a process. The tea roller was then evolved to roll the leaf mechanically on somewhat similar lines to the old hand rolling system, one machine being capable of doing the work of sixty men in the old hand method.

Modern Trough Withering

The chief process in rolling is to burst the leaf cells in which the sap is stored and this is accomplished by bruising or macerating the leaf without actually tearing it to shreds. The sap is thus liberated and coated over the surface of the leaf, so that, later when dried, the extracted matter remains coated on the surface of the leaf and can be easily dissolved by application of boiling water.

Air is allowed to come in contact as much as possible with the leaf during rolling, as the oxygen from the air oxidizes the leaf and turns the crude sap into palatable tea. As the leaf disintegrates, heat develops and this must be checked because excessive heat is detrimental to quality. Different rolling techniques are used for the different types of tea demanded by the trade.

Early Circular Roller

Rollers vary considerably in mechanical detail, but in principle they consist of a circular table with a hard surface on which brass or wooden battens such as the Lowmont or Salmond’s Battens are fitted.

The first tea roller imported into the country in 1876 was installed at Loolecondera and many others followed. A locally manufactured roller was installed at Hope Factory in 1878 by J.Walker & Company of Kandy. John Walker was the first engineer of repute to arrive in the island. He had started life as an engineering apprentice near Glasgow and after a varied and colourful life, he finally found his vocation as a designer of plantation machinery in Kandy, where he set up a construction business with his brother from which the Colombo firms of Walker Sons & Company any Walker & Greig are descended. The Walker Economic Tea Roller and the Colombo Pressure Dryer were originally introduced to Ceylon tea plantations in 1880.

The leaf is fed in from above through an open cylinder and as this cylinder rotates the amount of pressure applied to the leaf against the table surface can be adjusted. The pressure applied from the top and the rolling action of the two sections of the rolling table forces the leaf over the grooves, twisting and rupturing the cells. The leaf changes colour during rolling, gradually changing form green to a tinge of copper colour and during damp weather any excess of moisture may be expelled from the leaf during the rolling stages.

Modern Tea Roller

The leaf particles (dhools) collected after rolling are more or less in the form of balls of twisted leaf, which require to be broken up and the fine leaf separated from the coarse.

These are spread out on a table or sifter in the form of a rolling cylinder slightly inclined to the horizontal , the walls of the cylinder are formed of wire mesh which are graded along the inclined length of the cylinder.

Early Tea Sifting Process

The leaf is placed in one end of the cylinder and as the cylinder rotates gradually works done to the lower end, the finer leaf falls through the graded mesh forming the cylinder walls and is collected in separate grades. The large leaf that remains on top of the sifter is then returned to the roller for a second roll. The leaf that collects under the sifter contains a high proportion of small leaf particles and ‘tip’ which is essential for the production of quality tea.

The next stage is the process of fermentation; the rolled leaf is spread 10cm deep on a tiled ceramic floor for a predetermined period and as a result of their exposure to warm air, they start to ferment. This is a critical stage as over or under fermentation will result in poor quality tea. Fermentation brings about the changes necessary to make the tea palatable; the process can only take place when the cells of the tea leaf are properly ruptured. The liquor of under fermented tea will taste raw and green and that of over-fermented tea will come out soft.

Tea Leaf being placed in a Tea Dryer

The degree of colour, the quality and the flavor can be varied by adjusting the period of fermentation, humidity and temperature. The period of fermentation may vary from twenty minutes to five hours.

During fermentation oxidization takes place between cell constituents and the ambient oxygen which gives the tea its colour, strength and brightness. As this chemical process takes place the colour of the leaf changes to a bright coppery colour. Once the correct level of fermentation has been reached the tea is passed through a dryer to arrest further fermentation and to give the tea its characteristic black appearance.

Furnace fired with Eucalyptus logs

The first tea dryer in the country was erected at Windsor (Galamunduna) Factory in August 1882. Fast growing eucalyptus trees brought over from Australia were initially grown in the plantation for shade and when they reached maturity acted as wind breaks.

The trees were then felled and used for firing the factory boilers and any surplus timber was sold for making railway sleepers or firewood.

Marshall of Gainsborough, an establishment of international repute, also pioneered the installation of tea machinery in Ceylon, after completing a successful assignment in India. They joined hands with John Walker and Company and by invention and modification were able to provide tea rollers of various size and character to suit local requirements. The Jackson roller was one of their innovations. Davidson & Company in alliance with Mackwoods set up a workshop at Suduwella Mills for the production of tea machinery; their specialty was the Sirocco Dryer.

Modern Tea Sifter and Grader

The fermented tea then goes into the firing chamber, where hot air will dry it and prevent any further chemical reaction from taking place. It emerges hard and black, ready for grading. The keeping qualities of tea depend on the temperature at which the tea has been fired. The technology of tea drying depends on many factors, the most important being the firing temperature, the volume of air, the load of tea in the dryer trays, the period of drying and the inlet and exhaust temperatures.

Grading is the last but one of the processes in tea manufacture and determines the value of the final product. The tea particles are separated into different shapes and sizes, traditionally defined by trade requirements, y sifting through a progressively finer series of meshes. There are two main grades – leaf grades and broken grades.

Eucalytus trees on

Tea Estate

Leaf grade have larger and longer pieces of leaf giving lighter- coloured liquor. Broken grades consist of smaller pieces and normally give a darker liquor and stronger flavour. A third grade known as ‘dust’ containing the smallest particles of leaf is valued for its strength and quick infusion. Within these three grades are sub-divisions such as orange pekoes (leaf grades) and fannings (broken grades).

Where a large number of grades are produced by one factory, the grading process can be long and tedious; this is particularly so in low-grown areas, where it is not uncommon for factories to produce from twelve to fifteen grades.

The graded teas are finally weighed and packed into tea chests or paper sacks ready for dispatch to the broker’s store in Colombo. At the broker’s office they will be catalogued for the first available auction.

The early tea machinery companies certainly did their best to help planters in financial difficulties when the need to modernize their factories became urgent by offering them modern machinery at very attractive prices. Before long tea came to be cultivated at various elevations from over 2,100 metres to a few feet above sea level.

By 1883 Ceylon teas were freely discussed in Mincing Lane and soon came to be recognized as a product of exceptional good quality possessing the required amount of aroma and flavour, distinct from the light liquors of Chinese teas.

Auction of Tea in Mincing Lane

For more comprehensive information about Ceylon Tea, the Pioneers, Tea Factories, Planters, etc, please visit the following web site. www.historyofceylontea.com

1891 UK Census List

Name /Age in 1891/ Birthplace/ Relationship/ Census Place/ Census CountyBrowne, Keppel 17 Colombo, Ceylon Boarder Stratford on Avon Warwickshire

Brune, Louisa M 40 East Indies, Ceylon Lodger Appleshaw Hampshire

Bryde, Richard (Reverend) 47 Kandy, Ceylon Boarder St Marylebone LondonBuchanan, James 70 Trincomalee, Ceylon Father Liverpool Lancashire

Buckley, Joseph H 31 Kandy, Ceylon Head Clerkenwell London

.........

Butler, Samuel E 40 Colombo, Ceylon Head Combe Hay Somerset

Byrde, Alice Maburly 12 Matara, Ceylon Boarder Daughter St Peter Bedfordshire

Byrde, Arthard Alfred Ernest 18 Colombo, Ceylon Brother St Leonard Sussex

Byrde, Evans Maburly 12 Matara, Ceylon Boarder Son St Peter Bedfordshire

Byrde, Lens May Arbuthor 15 Point de Galle, Ceylon Boarder Daughter St Peter Bedfordshire

In the 1891 Census, the Reverend Richard Byrde and his children are in England.

In the Kabristan Archives “Graveyards in Ceylon – Kandy region Vol IV” on page 48 the following entry reads:-

A burial plot was purchased by Mr.E.M.Byrde (Evans Maburly Byrde – son of Rev: Richard Augustus Byrde) 14th June 1937 for Mr.H.W.Byrde.(Henry Byrde ** his cousin).

1 comment:

The transition from coffee to tea in Ceylon's history brought about challenges, including the need for efficient tea processing. Overcoming initial hurdles, planters established well-equipped factories, revolutionizing production. The meticulous manufacturing process, from withering to grading, ensures the purity and unadulterated quality that defines Ceylon Tea.

Post a Comment